The concert was great.

In case you're in need of an Al fix, here's the video of Trapped in a Drive Thru which is, of course, the parody of R. Kelly's Trapped in a Closet.

This is not a diary. It is a collection of thoughts, essays, stories, etc on those topics that are of interest to me. Being a blog, it goes without saying that it is utterly self-indulgent.

Labels: animation, funny, video, Weird Al Yankovich

A Shaolin temple, in China, is demanding an apology from an internet user who claimed that they were all once beaten by a ninja.

Correct me if I'm wrong, but isn't this the sort of thing that's usually settled with by an elaborately choreographed martial arts showdown?

Labels: Apology, China, Kung Fu, Martial Arts, Ninja

Labels: animation, Interview, video, Weird Al Yankovich

If you are a male geek, you probably know how disheartening it is to see that a lot of women prefer guys who are a bit more "conventionally cool". If so, here's an essay by a happy woman who urges her sisters to take a second look at us.

If you are a male geek, you probably know how disheartening it is to see that a lot of women prefer guys who are a bit more "conventionally cool". If so, here's an essay by a happy woman who urges her sisters to take a second look at us.

Among other things, she notes that we don't tend to hang out in bars, we're very good at remembering important dates and, lest we seem less than perfectly exciting, we're also very good at sex.

Of course, this does leave the question of how to spread the word. Somehow, I don't think that the internet is going to be the best way to get the word out.

Sometimes the best reply to ugliness is mockery.

Recently Tucker Carlson stated that he and a friend beat up a gay may who was "bothering him" in a bathroom stall -- a admission that was, astonishingly, met with laughter by his television colleagues. One can imagine the sort of outrage that would have been generated if he had said that he had beaten up a black guy or a Jew that had been "bothering" him.

Be that as it may, for all the justifiably angry responses that this has generated, my favorite is a witheringly snarky comment from a Fark forum:

"I can just picture him now, delivering an adorable flurry of overhand punches with his thumbs inside his fists."

Labels: Bigotry, homosexuality, Snark

Labels: Archeology, history, time

Once upon a time, when I was working at mail order company, my brain stumbled between the phrases "Hello, may I help you" and "Hello, may I put you on hold". What actually came out of my mouth was, "Hello, may I hold you?"

Oh, we all know how to say please and thank you and we may even know which side of the plate the knife and the fork go on, but does anyone ever offer any practical ettiquette advice for dealing with the truly awkward situations that life often finds us in? Well, fear not, The Awkwardness Survival Guide is on the case!

The guide offers advice ranging from the embarrassment of using an inappropriate term of endearment with your mother to how to handle your bewilderment when confronted with an ethnic handshake.

Take heart, fellow traveler; help is but a mouse-click away.

Labels: Advice, Awkward, Embarrassment, funny

Labels: Peter Cook, Puppet, satire, Thunderbirds

I hope that you have been enjoying my series of articles exploring various archetypes. I think that, for the time being at least, I’m going to take a break from the topic (although I would still welcome reader submissions), but I did want to take a moment to talk a bit about the overall topic.

The first thing that I should point out is that I’ve been telling you a lie. By expressing archetypes as a series of factual statements I have implied that a given archetype is something definite and definitive. Worse, I’ve suggested that some characters fit neatly into given archetypes (“He is Jimmy Olsen. He is Bonzo. He is Captain Crunch.”) I have compounded my sin by implying that characters can be an exact representation of an archetype.

In my defense, I have done this precisely because, too often, archetypes are described in such fuzzy terms that I think that they start to lose all meaning. Consider Carol Pearson’s set of twelve heroic archetypes (which includes Innocent, Orphan, Warrior, Destroyer, etc). Her descriptions of these archetypes are, in my opinion, perilously vague. What does it really say about the Orphan to say that his quest is “To regain safety”? I would guess that King Arthur would be an Orphan, but I can’t think of anything about his story that would suggest regaining safety. If it were just Arthur I wouldn’t complain but the same holds true of most orphaned heroes. To be sure, you can force a given hero into the mold (“By fighting crime, Batman's trying to regain the safety of his childhood…”), but such efforts smack of narrative contortionism.

My goal in expressing these archetypes in definitive terms has been to indicate that there is a there over there; that archetypes have a reality and that a given archetype means something, even if the precise meaning is open to interpretation and disputation.

The way that I think of archetypes is to imagine a map of characters. The archetypes would be represented as hills on the topology of the map. Depending on the popularity of the archetype, some hills with be taller – mountains in the terrain – and some of those mountains will have hills of their own or will themselves be part of a range of hills and mountains (the Hero would be such a range). Finding the precise summit of a given hill is difficult, however, because the terrain is complex, with many rills and rifts on every surface.

Because of this, no particular hero is going to be at the summit of his local archetype. Indeed, many heroes will find themselves in the valleys between peaks. Roland the Gunslinger is capable of facing any circumstance and is the master of himself and his surroundings, therefore he’s a Competent Man, but he’s also on a lifelong quest to find the Dark Tower and he’s the social equivalent of a knight in the terms of his own society so he’s also a Paladin. I believe that Roland’s camp is on the side of the valley facing the peak of the Competent Man but others might well disagree.

Characters also evolve. King Arthur starts his life as a Special Boy, but the boy who pulls the Sword from the Stone is not the same person as the man whose body is borne away to Avalon. The trajectory of a character through the archetypal map is every bit as significant as their location on that map at any given point in time. Guinevere’s life progresses from maiden to first love, to wife, to damsel in distress, to adulteress, to penitent. To fit her into a single slot would be to fail to appreciate the tragedy of her story. And even this isn’t a sufficient view. Does knowing that Luke Skywalker takes a hero's journey from orphan to knight tell you everything you know about his character? Of course not. A successful character is more than a few pounds of putty thrown over the scaffolding of his archetype.

I do not, however, want to suggest that archetypes are unimportant. They are a kind of narrative shortcut. When we see a James Bond movie, we can support Bond because we know that he’s the hero. The reason that we can believe that he’s the hero is because we subconsciously recognize that he has characteristics that we associate with the heroic archetype. Imagine what it would be like if every time you read a story you had to puzzle out the nature of every character from scratch. To be sure, a little narrative ambiguity (is this person really a hero?) can be a good thing, but even narrative ambiguity partakes of the short-hand of archetypes by presenting us with conflicting cues. This is also true of stories that subvert the archetype. Such stories rely on our recognition of archetypes to surprise us (“Oh my, it looks like the Sidekick is actually the Hero!”).

Without archetypes, narrative becomes impenetrable, as amply demonstrated by postmodern fiction that seems designed as nothing more than a sadistic effort to frustrate and piss off the reader. Never the less, reliance of archetypes can distort our perception of reality. Historical narratives are particularly vulnerable to false archetypal associations.

For years we thought of Christopher Columbus as the Great Explorer. Later, after the political climate changed, he was recast into the role of the Oppressor. The real person, however, is neither. He was a complex human being who was, by turns, heroic, mercenary, visionary, short sighted, oppressive, brave, and many other things besides, nor is it possible to understand Columbus without understand his world and culture. As it has been said, we are complex and contradictory creatures. When we tell ourselves our history, we should be aware that we want to simplify it; we want the narrative to conform to archetypal stereotypes and our desire for such a narrative will cause us to warp the narrative into a story.

Jung was convinced that archetypes were fundamental clues to the mystery of what is Man. While I have deep reservations about Jung’s psychological theories, to say nothing of his archetypal schema, I suspect that he was not that far off the mark with his intuition: archetypes do say something about us. I think that they may well be mile markers on the road to understanding our human nature.

We are man. We are woman. We are Humanity.

Labels: Archetypes, Essay, Human Nature, Narrative, philosophy

He is Cthulhu. He is Vulthoom. He is Q'yth-az. He is Hastur, He Who

He is Cthulhu. He is Vulthoom. He is Q'yth-az. He is Hastur, He Who

Must Not Be Named.....

Oh no!

AAAAAAAAAAAAARGHHHHHHH!!!

Labels: Archetypes, Great Old Ones, mythos

Labels: astronomy, Eclipse, Lunar Eclipse

He is the bankrobber. He is the minion. He is the kidnapper. He is the extortionist

The Thug is a man.

Although the Thug shares much of the demeanor of the Brute, he is fundamentally human.

The Thug has a soul, albeit a small one. This means that the Thug can be redeemed, but it is unlikely.

The Thug is not a threat to the Hero. Quite the contrary.

His purpose is demonstrate the prowess of the Hero. He is a paper tiger and a punching bag.

He is nameless. He may be called Bruno, or Boris, or what have you, but these are only labels. In truth, he is a slate.

He is stupid, but he is aware of his stupidity.

He admires the intelligence of the Boss. He despises the intelligence of everyone else.

The Thug wants sex but cannot easily find it. Woman are repelled by him. His only option is force or prostitution. He is a lousy lover.

His moral universe is divided between the weak and the strong. He bullies the weak and cowers before the strong.

He has no history. He was not born, nor does he have a family. When he is killed, he will be unmourned.

He is vicious but not Evil. He lacks the intelligence to be Evil. He is, however, drawn to Evil as a moth to a flame.

He is a willing thrall. A slave. He freely subordinates his will to that of the Boss.

He has a dim but determined sense of loyalty. It is a loyalty predicated on fear and worship.

The Thug has no taste. He wears cheap suits, he smokes cheap cigars and he drinks cheap beer. To the extent that he has any relationship with women, they too are cheap.

If he wasn’t a bully, he would be pitied. On a deep level, he knows this. That is why he bullies.

The Thug has no God except for the Boss. The Boss is a wrathful God.

Labels: Archetypes, Thug

Labels: Cool, cute, Immigrant Song, Kitten, Led Zepplin, video, Viking

Labels: Camelot, Monty Python, silly, Star Trek, video

He is the Cyclops. He is the Cave Troll. He is the Ogre.

He is male. He is, in fact, an exaggeration of masculinity.

The Brute is stupid. He is also evil. He is evil because he is stupid.

He embodies the Id. He destroys everything that he touches and revels in the destruction.

He is and agent of entropy.

There are only three things that he enjoys: eating, fucking and killing. If these can be combined, all the better.

He likes to fuck. He never asks permission to fuck. He does not perceive that this is rape, however, because there is no psychology to the act. He simply assumes that all women (and men) scream when they are being fucked.

The Brute is soulless. He did not sell his soul; he never had one to start.

He does not understand empathy or love. He doesn’t understand anything at all, really, except the aforementioned eating, fucking and killing.

Children are to be seen as appetizers.

The Brute is a monster but not a villain. He does not desire power or wealth. He is what he is.

The Brute may be employed by a villain. If this is so, the Brute neither understands nor cares to understand their relation. He will obey the villain only because the villain can hurt him.

The Brute can only be killed by a Hero or a heroic Sidekick. Anyone else who opposes the Brute will be killed, eaten and, perhaps, fucked.

He is too stupid to know that he is stupid. The Hero will usually exploit this.

The Brute is godless. The idea of God is beyond him.

Labels: Archetypes

Labels: Commercial, Japanese, Red Riding Hood, video

He is Sauron. She is the Baba Yaga. He is Voldemort. She is the Wicked Witch of the West.

He is a man. She is a woman. Neither is truly human.

They have vast power but their power is illegitimate and unholy. It was bought at the price of their soul.

They know things that Man Was not Meant to Know. This knowledge has corroded any remnants that have remained of their souls.

He is not to be confused with The Wizard who is a Mentor who knows magic.

If she is a woman, she is either a hag or inhumanely beautiful. If she is beautiful, she is only beautiful by virtue of her magic. She is, in truth, a hag.

He is old. If he appears to be young it is because he has used magic to preserve himself. Once the spell is broken he will be proven to be old and withered.

They are asexual. The only sexual acts that they will ever engage in will be as part of a dark rite. Any such acts will be perverse, shocking and blasphemous.

They have sold their souls to dark forces. They are damned and beyond any hope of redemption.

Although they have vast power, they will always crave more power, especially over others. This is the instrument of their downfall.

They believe in Good but they hate it. They hate it will a personal passion. Their choice to be Evil is deliberate and fulfilling.

They are sadistic. It is not sufficient to kill one’s enemies; they must be made to suffer.

They are Satanists. Even if they don’t worship Satan, himself, they worship Evil, which is the same thing.

Labels: Archetypes, Warlock, Witch

They took me down

To the Down

Where the river runs slow

and sour

Where reptile things,

Cold, slow and hidden,

Lurk in the thick of the mud

Where lost things go

To never be found

And they gave me an understanding

They could sink me down,

And whoever would miss me?

So I said what I said

To get out and away from there

And you know what I told them

I'm sorry, so sorry

That it had to be done

Now they're here for you

To take you to the Down

And it won't matter what I say

But I'll ask you anyway

When you're there

With all the lost and rotting things,

Would you say hello to my soul?

Labels: Poem

Thai police departments have been having a problem with officers violating minor rules such as littering and parking in prohibited areas. The departments have been reluctant to fire the officers but efforts to discipline them have proven ineffective.

Thai police departments have been having a problem with officers violating minor rules such as littering and parking in prohibited areas. The departments have been reluctant to fire the officers but efforts to discipline them have proven ineffective.

In the face of this, they've decided to attack the machismo of the officers by forcing them to wear Hello Kitty armbands as a mark of disciplinary shame. I have no idea if this will work about one only needs to ask dread Cthulhu about the power of the kitty.

Labels: cthulhu, Hello Kitty, news, Police, Thailand

They are the Argonauts. They are the Merry Men. They are the 300. They are Odysseus’ Men.

They are men. Manly men! Women can not be Companions. Don’t be silly.

They may be Heroes in their own right but the Hero will be first among equals. This is his story, after all.

They are there to help the Hero on his Journey which may or may not be a Quest.

They are manly but not gay. There is no hanky panky in the camp.

They are dedicated and loyal. They will see the Hero through to the end and follow him into the Gates of Hell if necessary.

They aren’t wimps. Grrr!

They are vulnerable. They can be killed. However, unless they are killed by a betrayal, they will not be avenged. They will, however, be mourned.

They may have Sidekicks. Their sidekicks will almost certainly die before the Journey is over.

They know how to party but they also know when to Get Down to Business.

They aren’t always the brightest bulbs in the bunch. Lucky the Hero is around.

Sometimes they will have a False Companion in their midst who will betray them. The False Companion will die as a direct consequence of his Betrayal.

They probably believe in God but who cares? There’s manly stuff to be done!

Labels: Archetypes, Companions

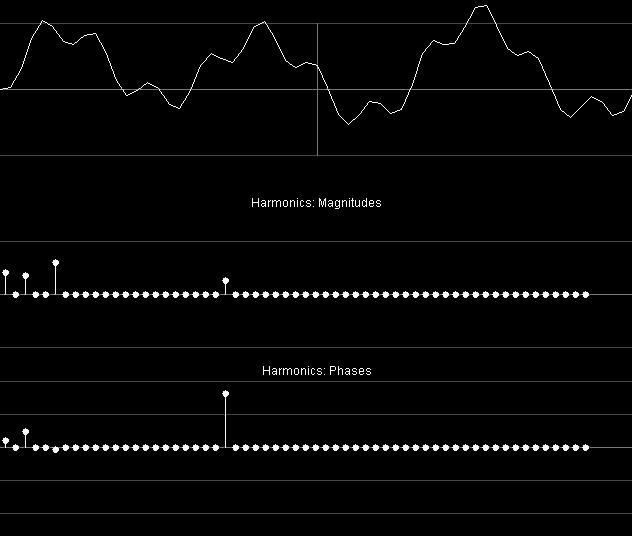

If you've ever played with an oscilloscope (and who hasn't!?), you'll love this marvelous applet that lets you simulate standing waves. The applet is part of the larger set of math and physics applets at Falstad.com.

I do believe that I have attained Nerdvana.

Labels: geek, oscilloscope, physics, Waves

Labels: animation, fighting, Stick figures

She is Cinderella's Step-Mother. She is the Wicked Queen.

She is a woman, but she has no womanly virtues.

She is evil. Worse, she is wicked.

She is a usurper. She steps into the place of the Good Mother, after the Good Mother dies, but she can not replace her.

She rarely has a name, only a title.

She is hateful.

She is jealous of the Good Mother’s child.

She is a witch and a bitch.

It is to be assumed that she is a slut and a whore, although we never catch her in the act.

She is a deceiver.

She wants to deprive the True Children of the Good Mother of their rightful place in the world. She wants to see them humiliated and killed.

She must be killed but only after she is humiliated.

She is dangerous and powerful.

She is an atheist and probably a Satanist.

Labels: Archetypes, Mother

It is a hungry gray cat. It is a white owl. It is a voyeuristic tabby. It is a bereaved walrus.

It is a hungry gray cat. It is a white owl. It is a voyeuristic tabby. It is a bereaved walrus.

The Lolcat is usually a cat, but not always. It may also be a dog, a furry rodent, or an aquatic mammal. Any cute mammal may be a Lolcat.

Owls may also be Lolcats. They were grandfathered in because an owl

was instrumental in starting the Lolcat craze.

The Lolcat is social. It always greets you with a friendly "Oh hai!"

The Lolcat is polite. It always says "Plz", "KThx", and "Scuze Meh".

The Lolcat likes to help you. It may clean your dishes, fix your pillow, buff your floors, even repair your computer. You may decide that its help is more trouble than it's worth.

The Lolcat has a Flavor. The Lolcat also knows that you has a Flavor, and seeks to taste it.

The Lolcat has no respect for personal boundaries. It will often get In Ur Property. Then it will start Doin Thingz to it.

The Lolcat may has a Title which relates to its appearance, disposition, or occupation.

The Lolcat can see Invisible objects and will often make use of them.

If a Lolcat is a cat, it has a Quest to find Cheezburgers. If a Lolcat is an aquatic mammal of any kind, it has a Quest to recover its Stolen Bucket. No other type of Lolcat has a Quest.

The Lolcat has Idiosyncratic Conjugation.

The Lolcat's favorite day is Caturday.

Beware a staring Lolcat. Its stare is a warning that It Is Not Amused. If you anger a Lolcat, you will soon need medical "Halp".

Labels: Archetypes, Lolcat, silly

I may give a more detailed review later on but, in the meanwhile, I want to encourage everyone to consider seeing the movie Stardust.

The trailers and commercials for the movie are, frankly, horrible. It doesn't seem like the people who are marketing it quite know how to handle what they have and the result is that they give the impression of something that's cheap and cheesy.

The actual movie isn't perfect (it takes about half an hour to really find its pace) but it is, in my opinion, a very enjoyable and often humorous fairytale (suitable for adults and children) with the sort of stylistic flourishes that one expects from Neil Gaiman.

Labels: Fairytale, movie, Neil Gaiman, Stardust

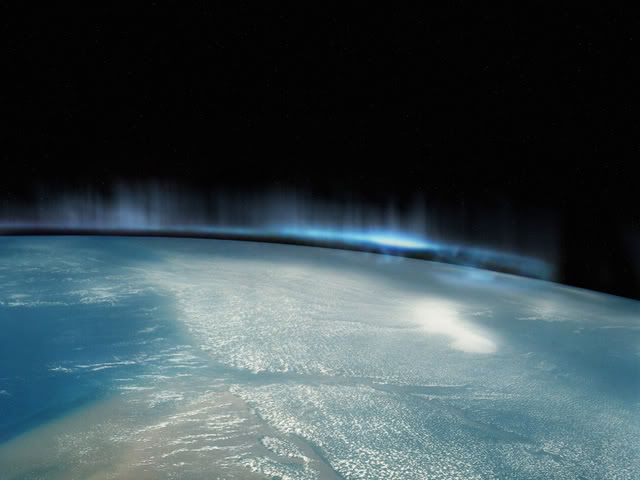

Labels: Aurora Borealis, Cool, photography, space

She is Gertrude. She is Mary. He is Geppetto.

She is Gertrude. She is Mary. He is Geppetto.

She is usually a woman but can occasionally be a man if he embraces feminine virtues.

She is the true mother. The Bad Mother may have usurped her, but she can not replace her.

She is nurturing and loving. She is not remote. This is her virtue but it is also her weakness.

She is to be protected by the Good Son.

She is to be despised and hated by the Bad Son.

She is the One True Love of The Father. It is never the Other One True Love of his.

She has no Legacy or Treasure to bequeath. She can only offer comfort and love. She may, however, pass only a bequeathment from The Father if he is absent.

When she is killed she is to be mourned and then avenged.

It is to be understood that she does not have sex with The Father. She is fundamentally chaste. This is a paradox and, yet, never the less true.

She is often a widow. If she is, she will remain faithful to The Father unless she is Seduced and Deceived.

If she is Seduced and Deceived, she will die, but not before she repents of her seduction and is forgiven because she is, of course, weak.

She is kind and charitable. This is part of her virtue but, again, also part of her weakness.

She wants to protect her children even though the Good Son needs to Go Out Into the World.

The Good Son has her love but can earn more by making her proud of him.

She is ageless but not old.

She is beautiful.

She believes in God. Her god is The Father.

Labels: Archetypes, Mother

Labels: Cool, Levitation, Science, Superconductivity

Many people consider it a social faux pas to bore your friends with stories about your dreams. I'm not sure I quite agree with that but I do agree that dreams have a way of seeming a lot more cool to the person who dreamed them than to the audience to whom they are being conveyed.

Many people consider it a social faux pas to bore your friends with stories about your dreams. I'm not sure I quite agree with that but I do agree that dreams have a way of seeming a lot more cool to the person who dreamed them than to the audience to whom they are being conveyed.

With that said, a segment of a dream I had last night just seems so darned cool that I feel compelled to share it, so brace yourself.

The background isn't really important. Basically, some unnamed female superheroine with a gun shtick has approached Batman for help. For reasons that weren't entirely clear to me, she needed to infiltrate a circus and she needed Batman's help with an act (which, apparently, they could do in costume... don't ask me why; this isn't the cool part).

So they come up with a kind of trapeze act where they're swinging around while trying to break bottles set up on a platform. First she shoots a few while tumbling through mid-air and then he breaks a few with his batarang until finally there's just a few bottles left.

Finally, he releases her into the air, throws his batarang, which hits and breaks two out of three of the bottles before curving back towards Batman. While the batarang and our heroine are both in flight she throws her gun into the air, the batarang connects with the gun, pulls the trigger and shoots the final bottle, all to immense applause.

Now tell me that wouldn't make an awesome comic-book movie moment!

Labels: Batman, comics, Cool, Dreams, superheroes

He is Victor Frankenstein. He is Henry Jekyll. He is Edward Mobius.

He is Victor Frankenstein. He is Henry Jekyll. He is Edward Mobius.

The Scientist is usually male, though the Scientist can be female.

In the Scientist's own eyes, his work is always for the Greater Good. He believes himself selfless. He is arrogant, though he clothes himself in modesty.

He secretly relishes the fame his success will bring him. He honestly believes he is in fact The Hero. Yet he loudly proclaims his own humbleness.

The Scientist is not crazy or power hungry. His Quest is not for domination. His Quest is not for power or riches. He is not a Mad Scientist, nor is he an Evil Genius.

The Scientist is not good; the scientist is not evil. The Scientist is focused on achieving his goal and success and nothing else.

Obstacles to his goal will be swept aside by his brilliance. Side-effects are unlikely or impossible.

The Scientist never achieves his goal. The Scientist always succumbs to his Great Mistake.

In the instant of his Great Mistake, the Scientist realizes nobody should pry so deeply into the Great Mysteries.

Though the Scientist is not evil, his Great Mistake creates Evil.

The Scientist is all the reasons we should remain ignorant for Our Own Good.

The Scientist is always ultimately destroyed by his Great Mistake.

He finds atonement only through self-sacrifice, helping The Hero stop the Mistake.

The Scientist is functionally celibate; he is not a family man, even when he has a family.

The Scientist is often the father of the Hero's One True Love.

The Scientist does not worship God. God is either superstition, or the Ultimate Mystery; in neither case does God deserve the Scientist's worship.

At the instant of his Great Mistake, the Scientist realizes God has always been there and that the Great Mistake is attempting to usurp God.

Labels: Archetypes, Scientist

He is Oberon of Amber. He is Abraham. He is Odin.

The Father is always a man. This may seem obvious, but it is not.

The Father is distant. The Father loves his children, but he is not close to them.

The Father children can be Heroes or Villains. When they are Villains they betray him and may murder him. When they are Heroes, they serve him and avenge him if he dies.

The Father is wise, powerful and frightening.

If the Father dies, he lives on in memory.

The Father does not intervene in the affairs of his children other than to express pride or disappointment.

The Father may bequeath a Treasure to a deserving son. That treasure may take the form of a Legacy.

All legitimacy flows from the Father.

The Father must not be questioned. To question the Father is to betray him.

The Father is not weak. If a father is weak, he is merely a parent.

It is possible for a Father to be fallible, but it is improper for a Son to point out his Father’s failings.

The Father is old. He is as old as time.

A Good Son will love his Father. Only Good Sons can become Heroes. Bad Sons who do not love their Father are doomed to become Villains.

A Father only has one Good Son. He may have any number of Bad Sons.

He may have daughters, but they are largely irrelevant except as items that his Good Son must protect.

The Fathers only overt expression of love is in the form of pride for his sons, which is reserved for those times when they have performed heroically and virtuously.

The Father does not believe in God. The Father is God.

Labels: Archetypes, Father

Well, it took a long time to happen but it seems that I'm finally starting to get hit with comment spam, so I've decided to turn on word verification for comments. You've probably already seen this "feature" on other blogs and forums; basically you need to prove that you are a live human being by copying a set of distorted letters whenever you post a comment.

For the record, I was hoping to avoid this. This blog is small enough that I didn't expect that I would be much of a target for spamming and I also consider word verification to be a bloody nuisance.

Please accept my apologies for the inconvenience. I do like the comments I get and I hope that this won't turn you off from making them.

Labels: administrivia

Labels: Clever, Sparta, street installations

Now that I've finished the Harry Potter series (and liked it very much, thank you), I've been stumbling around looking for reviews and commentary. I think the most thought provoking was a rather snippy piece written by Megan McArdle, an economist who complains that the economy of the wizardly world just doesn't make any sense. For instance she asks

Now that I've finished the Harry Potter series (and liked it very much, thank you), I've been stumbling around looking for reviews and commentary. I think the most thought provoking was a rather snippy piece written by Megan McArdle, an economist who complains that the economy of the wizardly world just doesn't make any sense. For instance she asks

Why are the Weasleys poor? Why would any wizard be? Anything they need, except scarce magical objects, can be obtained by ordering a house elf to do it, or casting a spell, or, in a pinch, making objects like dinner, or a house, assemble themselves. Yet the Weasleys are poor not just by wizard standards, but by ours: they lack things like new clothes and textbooks that should be easily obtainable with a few magic words. Why?While I have no doubt that a sufficiently motivated Potter fan could come up with a plausible theory of wizardly economics, I'm sure that the real answer is that Rowlings never really put much thought into it.1 Indeed, I think that many high fantasy works are going to suffer the sin of having unrealistic economies. Be that as it may, I thought it might be fun to briefly consider the economies of few fantasy worlds to see if we can answer of the question of the Weasleys poverty in their contexts and to address the question of how we can have a system of economics in a fantasy setting that allows for the existence of a family such as the Weasleys.

They are Romeo and Juliet. They are Antony and Cleopatra. They are Jack and Rose.

They are of both genders, but never of the same gender.

They can be both Hero and Victim.

The Lover’s story is tragic and romantic.

The Lovers are defined by their Beloveds.

Every lover is a Beloved.

The Beloved is similar to but distinct from the One True Love of the Heroic cycle.

The Lovers are both driven by and at the mercy of Fate.

Their moral universe is divided between their Beloved and all that stands between them and their Beloved.

Their love is pure and virtuous. There is a sexual component to the love but only in as much as it is an expression of love. Be that as it may, the erotic aspect can be charged and may take many forms.

The lovers will often die before they can consummate their love for one another.

They are young, naïve and optimistic.

Their love always takes the form of love at first sight.

If there is a Villain, the Villain’s goal is to keep the Lovers separate and to destroy their love. If there is no Villain, Fate will play this role.

A lover will either die in the arms of his beloved or at her side.

In the cases where one lover survives, it shall be the woman.

The Lovers are more prone to think about Heaven than God.

Labels: Archetypes

This story is a "Best of the Blog" repeat.

Labels: Best of the Blog

Today's article is a "Best of the Blog" repeat.

Science is a form of epistemology that, like any good epistemology, attempts to distinguish true statements from false statements thereby leading to an accumulation of knowledge. One of the primary things that distinguishes science from other epistemologies is that it is a) systematic and b) nondogmatic. A proper science must have a means of validating its claims as well as a means of identifying and rejecting false claims. This, too, ought to be systematic.Let us agree to this definition, and also agree that here "true" and "false" refers to an objective agreement with the 'outside' world.

Labels: Best of the Blog