There is a shatter of leaves

Declaring the wind.

There is a brief temptation

To blow away with them.

Thursday, March 31, 2005

Tuesday, March 29, 2005

Theotest Challenge Redux

A while back, when I was still in the habit of debating atheism, I came up with something that I called the theotest challenge. Essentially it was a promise to convert to the religion of someone's choice if they could tell me the contents of an encrypted file (presumably by praying to their god for the answer).

It's been quite a while since I've engaged in doing those kinds of rhetorical stunts. I am greatly amused, however, to see that the Atheological Thinking site, run by one Silent Dave, has not only taken up the torch but has done me the honor of naming a modified version of the challenge after me. He's also tightened it up a bit. Many people were skeptical of my claim that I would convert (which I could well understand). In this version of the challenge, he promises to "either read four books of your choosing or attend a church of your choosing for four months, and [he] will give $100 to the American Red Cross!"

The challange can be found here. Scroll down almost all the way to the bottom to find it, or just do a search for "Lias".

Labels: atheism

Monday, March 28, 2005

My One and Only Comment on the Schiavo Case

Back in the late months of 1993, I discovered Usenet and a penchant for online debate. Like many people, I find debating to be invigorating and useful. I have previously compared debate to a kind of crucible that we can use to test our beliefs against the beliefs of others with the hope that the crucible will allow us to retain good beliefs while rejecting bad beliefs.

I will speak with no false modesty: I became a good debater. I learned, early on, that the best way to do well in a debate was to restrict myself to debating those subjects where I had a good understanding of the topic.

It seems like an obvious maxim but it’s clear that it’s one that many people don’t get. Too often, people feel compelled to weigh in on topics which they clearly don’t understand. It wouldn’t be so bad if such people limited themselves to questions and an effort to enhance their understanding but, typically, they tried to be pundits and ended up being transparently ignorant. Such people are pathetically easy to best in a debate (even when they obstinately refuse to concede a point). They are also uninteresting to debate for this very reason. It was a proliferation of such pseudo-pundits that ultimately killed off most of my desire to engage in online debates. The quality of the argument was so low that I wasn’t getting the benefit of the crucible.

Be that as it may, as I’ve transitioned from debate to essay writing, I’ve kept this basic principle in mind: talk about what I know, qualify what I don’t, and leave the rest to the experts.

Everyone seems to have a passionate opinion about the Terry Schiavo case. Like most of you, I am aware that Terry Schiavo fell into a coma fifteen years ago. I know that her husband petitioned the courts to have her feeding tube removed. I know that her parents opposed the petition. I know that the courts determined that Ms. Schiavo was in a persistent vegetative state. I know that various doctors have supported and opposed this conclusion. I am aware that the case has been appealed up through the courts and that the courts have continued to side with the removal of the feeding tube. I know that both the Florida legislature and the US Congress have weighed in on the issue and have, for the most part, sided with the family. I know that, as of this writing, the tube has been removed and that Ms. Schiavo, pending any successful attempts to have her feeding tube reinserted, will soon die. I am aware that various allegations have been made concerning the motives of her husband as well as the motives of her family. I am aware that this issue has become enmeshed with the larger issue of the right to life and the right to die campaigns and that this has been a subject of very emotional controversy.

This is what I know.

I do not know whether or not Ms. Schiavo is in a persistent vegetative state or a state of “minimal consciousness”. I do not know if her husband is acting on behalf of her interests or on behalf of his own. I have seen a CAT scan that would seem to indicate that her frontal lobe has liquefied. I do not have the expertise to interpret the scan. I have seen video of Ms. Schiavo apparently responding to various stimuli. I do not have the expertise to know whether or not these reactions indicate genuine consciousness or instinctual reflexes. I have read opinions on both sides from a variety of neurologists and do not have the expertise to know which opinion is more informed. I do not know whether or not Ms. Schiavo would have wanted to live under these circumstances.

Ultimately, I don’t know a lot about this case.

The curious thing is that a whole lot of people who aren’t doctors, or members of her family, and who have not had any direct involvement in the court proceedings have, never the less, expressed some very confident opinions regarding this case, one way or the other. Some of these opinions are nearly psychic, claiming to express knowledge of the state of Ms. Schiavo’s personal beliefs in the matter. Indeed, one of the more remarkable (and remarkably stupid) opinions I’ve seen has been that of so-called psychic John Edwards, who, until recently, had a show where he claimed the ability to talk to the dead (and, apparently, the comatose).

I am doubtful that many of the people who have firm convictions regarding this case have, in fact, a firm foundation for those convictions. My own conviction is that this is a sad, sad matter but one that is, ultimately, none of my business. I didn’t know Terry. I wasn’t there when she supposedly expressed a wish not to live in such a state. I wasn’t there when she was being diagnosed (nor would I have known how to evaluate the diagnosis). I was not there when the case made it through the courts. I do not, in truth, know whether the courts have made the right choice. Given this, how can I possibly decide whether or not this person should have her feeding tube removed? I don’t have the means to know whether this is an act of mercy or an act of cruelty.

All I know is that one of the reasons that we have courts, as well as a system of appeals, is that someone has to have the unhappy duty of making such decisions. I do not believe that the courts are infallible. It is plausible that something morally wrong is being done. It is just as plausible that failing to do this would be just as wrong. I have no choice but to accept the verdict of the courts and to hope that they have done the right thing.

The alternative would be to pretend to an expertise that neither I, nor the majority of people, have.

Sunday, March 27, 2005

Off-site Essay: The Relativity of Wrong

As I mentioned in last week's essay, I'm am switching to an every-other-week schedule for my Sunday essays. As I also mentiond, I do want to do something on the Sundays when I'm not posting an essay. I still haven't settled on precisely what I'd like to do, but I want to experiment with the idea of posting pointers to good off-site essays.

Isaas Asmiov was one of the most prolific writers of the twentieth century. In addition to being an acclaimed science fiction author, he is credited with writing over five hundred books (the exact count depending on how one counts his anthologies and collections where he was the editor). He was an equally prolific writer of essays. As impressive as the quanitity of his writings is, the quality of his work is just as remarkable. This is especially true of his intellectual popularizations. Asimov was justifiably considered a polymath and may well have been among the last of the world's rennaisance men, publishing to every category of the Dewey Decimal system with the sole exception of philosophy.1

Of all his essays, my personal favorite is one titled The Relativity of Wrong. Many critics of science assume a naive stance of belittling science because science has a history of proving itself wrong time and again and, therefore, it is insinuated that we shouldn't put any trust in current theories because they could all be overturned during the next paradigm shift. Asimov deftly illustrates that "wrong" is a relative term and that the implicit assumption that wrong is an absolute mischaracterizes the way that science works.

I hope that you enjoy the essay as much as I have.

1 Although none of his books dealt with philosophy, I would suggest that The Relativity of Wrong is about nothing less than epistemology.

Labels: epistemology, Essay

Thursday, March 24, 2005

Eight Legs

I used to play with spiders.

I would throw insects,

Into their webs:

Miniature sacrifices

To a child-size

Aztec pantheon.

Sometimes I would tease them

With twigs, twine, and debris –

Mock bugs sacrificed in effigy.

Then the dreams.

Perhaps I offended

Some arachnid god

With my impiety.

There were carpet crawling swarms.

There were things the size of dogs.

There were things the size of houses.

There were other things,

Worse things.

When I startled myself awake,

They would often scurry

Out of the nightmares:

I could feel them

Crawling between my sheets.

I envy arachnophiles.

I wish that I could see

Through their eyes,

Through my former eyes,

The graceful, beautiful efficiency,

The cruel indifference,

The magnificence.

But I can’t.

My Hell

Has eight legs.

Labels: arachnophobia, fear, Poem, spider

Tuesday, March 22, 2005

Mike, the Headless Chicken

It is said that truth is stranger than fiction. Well, I read a fair amount of rather strange fiction, so I'm not generally inclined to accept the saying without good evidence to back it up.

Sometimes, however, reality does live up to the aphorism. Here is the tale of Mike, the Headless Chicken.

Sunday, March 20, 2005

An Unstructured Year

Blogger, in their effort to encourage the art of blogging, periodically publishes articles whose intended function is to give advice and words of encouragement to the bloggers that use their service.

Last September they published an article on how one should go about promoting ones blog. Included in the article were a number of suggestions on how to make a blog successful. Two, in particular, have stood out in my memory:

- Keep your blog on topic

- Keep your posts brief

For nearly a year now, I’ve been publishing poems, pointers to various sites, and all sorts of random thoughts and observations on any number of things. On a regular basis I have also (though not without the occasional lapse) been posting weekly essays on topics ranging from the moral basis of law with regards to the question of free will to the subject of what philosophers have to say about telling the difference between one’s ass and a hole in the ground. My essays have ranged in length from short ones barely over five hundred words to monsters exceeding seven thousand with the majority falling somewhere between fifteen hundred and twenty-five hundred words.

According to Blogger, my blog should not be a success. So, is it a failure?

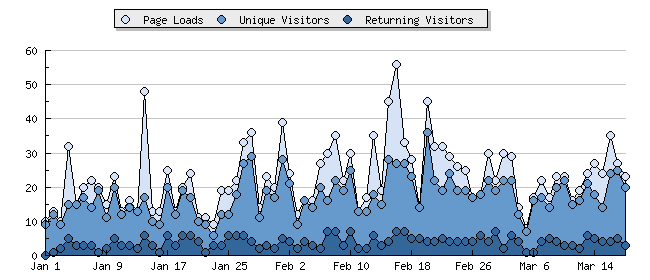

Like many blogs out there, I employ a tracking tool that helps me see how many hits I get as well as some basic information on the sorts of hits I get (see chart). On an average day I get about 20 unique visits. Of those twenty, about 5 will be from returning visitors (although that can be difficult to estimate). Of the new visitors, an average of two will click through to the archive. Looking at overall hit indicators, I would guess that I have about fifteen regular visitors and another ten who come here semi-regularly (although there is a lot of inference involved in coming up with those numbers).

In terms of sheer popularity, this would suggest that I do not, in fact, have a successful blog. If I were actually attempting to make money off of the blog, for instance (say via click-thru advertising), I might have enough traffic to grant me the cost of a candy bar a few times a year. Nor am I getting the sorts of numbers that would allow me to see myself as any sort of popular pundit. If I were doing this for the sake of having a wide audience to gratify my ego, I should have taken down my shingle within the first few months.

Fortunately, my standards of success aren’t entirely dependant on the size of my audience. I want to be clear that when I say it isn’t entirely dependant that I do place value on having an audience. If that weren’t the case, there would be no need for me to publish these musings of mine online. There certainly wouldn’t be a good reason to keep posting essays week after week. While I do esteem my audience (especially those regulars who have deigned to put me in their bookmarks), I would much rather have a thoughtful audience than a vast audience.

In the interests of full disclosure, I should admit that it took me awhile to realize this. When I started Unstructured Musings, I genuinely did hope that I’d have hundreds of people hanging from my every word. When I didn’t see those numbers, I grew concerned and tried to employ a few gimmicks. Back in June I spent some money on a service that promised to deliver unique hits to the site. The site did exactly as it promised. For several months, I’d regularly get well over a hundred hits. The problem was that none of them ever seemed to return and few of them even bothered to click to the archives. Examining where I was being hit from helped to explain why. My of my hits were coming from outside the US. I doubt that most of the people who came to me via that service even spoke English. Of those who did, it seemed apparent that few of them would have had any interest in the content of the site once they got here.

Then there was the Gmail contest that I held back in June. This was back when Gmail accounts were still hard to come by and people were willing to go to some lengths to get them. I offered a free gmail account to whoever posted the most insightful comment to any of my essays. I got a handful of takers, all of them exhibiting the bare minimum of effort necessary to constitute a reply. In retrospect, my little contest seems pathetically desperate.

Since then, I’ve learned to relax and allow my readership to grow naturally and it has, in fact, grown. Looking at the graph over the whole of the year, I’ve been getting a slow but steady increase in hits. Even more gratifying, I’ve finally started getting comments and feedback on a fairly regular basis — again, not a lot, but enough to deduce a trend. Better yet, the quality of the commentary has been very high. The people who have taken the time to reply to my essays have clearly put a lot of thought into their replies, which thrills me to no end. I’ve also spotted a number of unsolicited reviews of the site which have been uniformly complimentary.

Even though I’m not reaching a lot of people, it does seem that I am making a good impression on those people who I am reaching. I am proud that I have an audience of people who are intelligent and thoughtful, who take the time to give my musing consideration, and who are having their thoughts provoked by my essays.

For me, this is success. I could not have, in all earnestness, hoped for more.

It is at this point that I want to thank you for being with me this last year. It is also at this point that I need to announce a change to the site.

When I started doing this, I committed myself to a very ambitious schedule of posting once a week. I made the schedule even more ambitious by adding in weekly posts for poetry and interesting sites and then compounded that by launching the Unstructured Poems sister site. As I was doing all this, I wondered if I were crazy. In retrospect, I am certain that I was. I enjoy writing essays but an essay a week is a grueling schedule, especially considering that this is an unpaid hobby. While I have no regrets for the last year, I have to confess that this is a schedule that I can no longer maintain. In addition to a new and demanding (although enjoyable) job, I have also found that the effort of getting these essays out has been cutting into my home life and my reading time. This last is particularly frustrating given that it is my readings that, ultimately, provide the inspiration for the majority of my essays.

I am not quitting, but I am cutting back. Instead of a weekly essay, I will try to get a fresh essay out once every other week. Tuesday Fun and the Thursday Poetry Slam will remain on the same schedule. I would also like to continue providing something every Sunday. One idea I’d like to try out is providing pointers to quality offsite essays every second week (as I did two weeks ago). I’m also going to try and see if I can solicit some guest essays once in awhile. Any other thoughts or suggestions are certainly welcome.

Be assured, I am not throwing in the towel. Writing Unstructured Musings has been one of the definite high points of this last year and I intend to continue publishing it well into the future and I hope that you will continue to read it so long as I continue to write it.

Here’s looking forward to another wordy and topically unfocused year.

Thursday, March 17, 2005

How Like a Thunderstorm

How like a thunderstorm.

Beginning in temperate times,

Warm words float

With a gentle laze

Between her and him,

From him to her,

Refreshing in their kindness,

But, already, there is a wind,

With the faintest chill

Carried across the undertones,

Cutting, slowly,

Across their skin.

Then comes the rain;

Tears dash themselves

To the ground

Like a suicide of regrets,

And the air is cold,

And gray,

Between them.

Before too long,

Hot, jagged words

Flash from mouth

To ear to mouth,

Sizzling with anger,

Thunderous with recrimination,

Blinding in their intensity.

Blinding and frightful.

What is next is inevitable:

That one of those words

Strikes the dry kindling

Of insecurity and sensitivity,

Bringing forth a conflagration

That mere tears cannot quench.

Tuesday, March 15, 2005

Unstructured Superdickery

We seem to have a curious relationship with our heroes. On the one hand, we venerate them while, on the other, we desire to bring them down to our own level.

An interesting and amusing exhibit of this latter trait can be found at Superdickery.com which features a collection of comic book covers that "prove" that Superman is, in fact, a dick.

My favorite is a cover with Superman and Jimmy Olsen. Superman is holding up a jacket that Jimmy got him, burning it with his heat-vision. As he's doing this, Superman says, "Jimmy, this gift you got me for Father's Day makes me sorry that I ever adopted you as my son. I'll have to destory it to teach you a lesson!"

The pedant in me does feel compelled to note that comic covers are intended to compell kids to buy their issues and that a common trick is to depict characters behaving contrary to their personas. Never the less, it's a very amusing collection of covers.

Enjoy.

Special thanks to Natalie Ramsey for the link

Labels: comics, Humor, satire, superheroes

Sunday, March 13, 2005

The Force of Habit, part II

This is the second part of a two part essay. In the previous installment of the essay, I told an anecdote about habit and alluded to Hume’s belief that habit was sufficient, and necessary, to account for human beliefs and behaviors. In order to explain this, I took a brief explanatory journey through philosophy, epistemology, logic and deduction, ending with some observations regarding the limitations of deductive logic.

To recap, logic is intended to be a kind of truth mill. One of the limitations of deductive logic is that it can be argued that it doesn’t provide a mechanism to discover new truths so much as a means of clarifying our existing assumptions. This is because the conclusion of a deductive argument is already encapsulated in its assumptions.

Induction attempts to allow us to reach new truths by allowing us to reach conclusions which do not necessarily follow from their premises. It is important to stress that I am using the word “necessary” in a strict technical sense to mean something that logically required. In deductive logic, if we accept the premises of an argument, we are rationally constrained to accept the conclusion. The conclusion, in this sense, is necessary.

Where deduction offers us necessities, induction can only offer us probabilities. The cornerstone of inductive argumentation is the notion of inference. To illustrate the difference, let us consider the question of whether or not lions are carnivorous. Let us suppose that we have observed, over the course of years, any number of lions eating meat. If we constrain ourselves to deductive arguments, the only conclusion that we can draw from our observations is that some lions are carnivorous some of the time. No matter how many lions we’ve observed and no matter how often we’ve observed them, deduction does not allow us to logically discount the possibility that there is some population of lions that eats plants or that the lions that we’ve been observing are herbivorous when we aren’t observing them. Induction, however, allows us to infer, via our observations, that lions, as a whole, are carnivorous.

It should be immediately apparent that a strict reliance on deduction may not be able to tell us very much about the world and, furthermore, that what it can tell us will be hedged around with innumerable qualifications and caveats. Induction, by contrast, can allow us to make conclusions about the world that we could never reach through a process of strict deduction (citizens of the planet Vulcan to the contrary). There is a price to be paid though: certainty. While induction allows us to draw non-deductive conclusions, the conclusions are in no sense necessary. To illustrate this, we shall turn our attention from lions to swans.

Throughout most of the world, including Europe, Asia and Americas, swans are white. A natural philosopher from, say, the fifteenth century would have been perfectly within his inductive rights to infer that swans, as a whole, are white (with only the exceptions of diseased, deformed or altered animals). The preponderance of observation would have supported his conjecture. He would, however, have been wrong. Australian swans are black. With the discovery and exploration of Australia, the inductive inference would have been revealed to have been a leap to an unreal conclusion.

Bounded by swans and lions, we come to the question of confidence. It is unfair to criticize induction for failing to be infallible. Inductive logic never promised infallibility, it only offered to provide us with conclusions that we could put a degree of confidence in. There, however, is the central question: how much confidence can we put into our inductive conclusions. This is where Hume enters the picture.

David Hume was a Scottish philosopher who lived in the 18th century. It must be stressed, up front, that Hume’s critiques of reason were not motivated by a hatred of rationality. Quite the contrary, Hume had a sincere desire to believe that a) humans were rational beings and b) that the universe was amenable to rational inquiry. Hume lived in an era where science was coming into a state of intellectual prominence. Science, at its heart, is an inductive philosophy. In simplified (very simplified) form, a scientist makes observations, forms a hypothesis, and performs experiments which seek to demonstrate of invalidate the hypothesis. The notion that observations can lead to a generalization (i.e., a hypothesis) is essentially inductive as is the notion that any amount of experimentation could validate the hypothesis (where deduction would insist that any given experiment could only logically apply to the specific circumstances of that particular experiment). Hume knew that induction was a powerful tool and wanted to demonstrate that it was rationally defensible.

Hume saw that one of the most productive methodologies of science was something called reductionism. This is where one takes a system and attempts to understand the system by reducing it to its parts. One might imagine a person seeking to understand the mechanisms of a pocket watch by carefully taking it apart and examining the cogs, gears and springs that comprise it. 1 Hume sought to take the methodology of reduction and to use it to parse apart the component elements of reason.

The first thing that Hume did was to consider the question of causality. Causality is the property whereby a cause can be used to explain an event. If I kick a football (cause) it will be launched into the air (effect), for instance. Since many of our conclusions stem from the assumption that there is a causal relationship between events, Hume wanted to show that we could rationally rely on causation. Hume wanted to demonstrate that there is a necessary, logical relation between causes and effects (note the necessary clause – we’ll come back to that). I won’t detail his efforts except to note that he was vastly disappointed to discover that, no matter how he tried, he could not. The most he could conclude is that humans have an expectation that some events have a causal relation. If I put a pot of water over a fire, I expect that it will boil in due time. In Hume’s analysis, my expectation that the pot will boil can not be rationally justified.

From here, Hume considered the broader question of induction. How can any amount of observation lend itself to a conclusion, even if the conclusion is only expressed in terms of relative certainty?

One possible justification was to assume that the future must resemble the past. If the sun has risen throughout the course of human history each and every day, shall we not be confident that it will also rise tomorrow. Hume demonstrated, however, that there was nothing logically inconsistent in the notion that the future may diverge from the past regardless of how long the past has been consistent. Indeed, the notion that the past leads to a consistent future is little more than the assumption of causality rephrased.

Okay, if we can’t deductively affirm the future, might we not inductively do so? If the future has been consistent for billions of years, isn’t it probable that it will continue to be consistent tomorrow? Is this not an allowable inference? Ah, but now we’re trying to use induction to prove induction and that is nothing more or less than circular reasoning.

Hume’s sad conclusion was that although we do, in fact, heavily rely on inductive rationales, we have no rational foundation to our reliance. So, Hume asked himself, why is it that we do rely on them so persistently and insistently? Are we not, after all, rational animals? Hume decided that the only possible answer is that we were not rational animals. Our reliance upon causality and induction, in Hume’s view, ultimately came down to a single thing: habit.

In Hume’s thesis, humans were little more than bundles of perceptions bound by a sense of habit that was instinctually engraved within us. If we avoid sticking our hands into fires, it is not because we have rationally concluded that we will burn ourselves if we do, it is because we have a habitual aversion to fire. If we avoid leaping in front of fast moving vehicles, it is not because we have rationally inferred that we would likely be killed, but because we have developed a habitual avoidance of doing so. If, indeed, we believe that causes precede effects or that there is, in fact, such a thing as causes and effects, it is simply because we have grown accustomed to seeing the universe in such term. Latter day Humeans would go so far as to proclaim that the belief in cause and effect is nothing more than a kind of superstition.2

Was Hume right? I would say that depends on how we evaluate his thesis. I believe that Hume’s ultimate objection comes down to a desire that the induction can be deductively justified. Note Hume’s contention that there is no necessary relationship between the past and the future. The desire for necessity is a central hallmark of deductive logic. Since we already know that deduction can not lend itself to conclusions that aren’t implicit in its premises, I don’t think that we should be surprised that it can not be used to validate an epistemological tool whose primary function is to allow us to reach conclusions that aren’t entirely implicit within their premises. In this sense, we are criticizing a hammer for not being a screwdriver.

Hume’s observation that using induction to support induction is, itself, circular does carry more weight. He is correct. We can not induce that induction is reliable for the very reason that it is the reliability of induction that is being questioned.

Here, I think, we must take a step back and ask ourselves what is meant when we say that something is reasonable. What, in fact, is this reason and rationality that we’re attempting to approach? Here we enter very murky waters. Some have narrowly defined reason has the human faculty for logic. If that’s the case, anything that qualifies as logic is, by definition, a basis for rational thought. The question then becomes one of whether or not induction is a type of logic. It is, at this point, that philosophy devolves into semantics. Some people define logic in terms of deduction claiming that anything that is non-deductive isn’t logical. Well, if that’s the cause, then it is tautological that induction isn’t reasonable, nor did we need Hume to challenge it. Others, by contrast, say that induction is, in fact, a form of logic. Again, we’re dealing with tautologies. If reason is the use of logic and induction is logic, then using induction is reasonable by definition. Clearly this isn’t a helpful line of inquiry.

George Lakoff and Mark Johnson have recently proposed a much broader conception of what reason is. They suggest that reason is “not only our capacity for logical inference, but also our ability to conduct inquiry, to solve problems, to evaluate, to criticize, to deliberate about how we should act, and to reach an understanding of ourselves, other people, and the world.”

I would summarize this as saying that reason is our capacity to reach conclusion via a methodical (and even methodological) process of thought. Reason is not infallible and, in fact, it is not always reliable but, when all is said and done, we have causes (good, bad or otherwise) for believing as we do. When Hume dismissed causality from the picture, he dismissed reason. The foundation of reason is, in fact, an assumption. It is the assumption that we can have cause to believe our conclusions. Like a logical axiom, this can not be demonstrated externally but must, instead, be accepted in the abstract. Sans that acceptance, reason can’t exist. Sans that acceptance, asking if we have cause to believe in reason isn’t even a coherent question since the predicate of the question is, itself, founded on the assumption that one ought not believe things without cause.

We do not live in an abstract world. We live in a concrete world. In the world we inhabit, fires don’t merely burn us theoretically nor do fast moving vehicles only impact us in terms of abstract hypothetical scenarios. We live in a world that requires us to interact with it. If our interactions are based on faulty evaluations (ergo, reasons), we can very easily be killed by our attempts to interact with it. In these terms, the inductive assumption, along with the causal assumption, aren’t merely conveniences of habit that we have adopted out of some indelible instinct, they are instruments of survival.

If we dismiss them, we are left with a world that is much like a car where the controls could be randomly reversed from moment to moment. In such a car, nothing you do could possibly matter because any attempt to accelerate or break or steer could cause you to crash. If you were to assume that your car was that kind of vehicle, it would be literally impossible to drive it. The only way that you can get from point A to point B is to drive with the assumption that turning the wheel a given direction will steer the car in the same direction, that one particular pedal accelerates the car and another decelerates it, and so forth and so on. Even when your assumptions are betrayed (say by a cut brake line) you need to have those working assumptions as a default. The alternative is a paralysis of action.

The world requires us to make decisions. Reason and all of its tools, including induction, allow us to make those decisions. They represent our best effort to do so and we judge their success by our continuing survival. To reduce this necessity to a cluster of habits wrapped around a bundle of perceptions is, I believe, an error of its own kind.

1As a quick aside, there are a lot of ignorant criticisms of reductionism that are little more than lampoons of this method by implying that reductionists invariably miss the forest for the trees. The goal of real-world reductionism is to take the knowledge of a systems parts and to recombine those parts into a new synthesis that allows us to understand the whole in terms of the interaction of its parts.

2This conjecture isn’t one that’s solely embraced by philosophical dilettantes and fuzzy-headed mystics. Among its proponents were such heavyweight philosophers and rationalists as Bertrand Russell.

Labels: epistemology, Essay, induction, logic, philosophy

Thursday, March 10, 2005

Lines

How do I define these lines

That crisscross through us

And out the other side

Connecting

Him to her

To you to me

To them to we

To us

As our nervous systems

Twitch in sync

As our hearts

Jolt us each to every one

As our whispers

Flow fast and free

I breath in

And you exhale

Labels: connections, Poem

Tuesday, March 08, 2005

Unstructured Fun

Sometimes, or so we are told, it is important to think outside of the box. At other times, it's necessary to think inside of the disk, or at least that's what the uninspiringly named but exceedingly addictive Breakout variant Plastic Balls 1.5 would have us believe.

A Flash Player is required to play this game.

Saturday, March 05, 2005

Off-site Essay: The Panopticon Singularity

I'm afraid that I've had a rather busy week. As a consequence, part two of last week's essay isn't in a state that I feel very good about publishing.

In exchange for your patience, allow me to provide a link to an alternative and thought provoking essay by Charles Stross called The Panopticon Singularity.

I think you'll enjoy it.

Labels: Essay

Thursday, March 03, 2005

Guilt

Every pain is a memory;

Every ache is a regret.

Guilt like sour milk,

Discovered in the aftertaste.

I say my sorrow,

But it’s only another rebuke.

Tuesday, March 01, 2005

Review: Constantine

Since I welched on last weeks Tuesday Fun, I thought that I’d make up for the lapse with a review on the movie Constantine.

Constantine is based, more or less, on the Hellblazer series of comics. Hellblazer is part of DC Comics Vertigo line which is what they use to publish their adult-themed comics. I was actually a fairly big fan of the Hellblazer series back in the days when I had the time and money to indulge a comic book hobby (I shudder to think of all the money I spent collecting rare editions).

In the comics, John Constantine is a sort of modern-day mage with a heavy involvement in the war between Heaven and Hell. Although he is a damned soul, due to his indulgence in various dark rites, he’s very much on the side of the human race in assisting it against malevolent forces. The movie version of Constantine more or less retains this conception of him with relative faith. I would make a minor quibble of the fact that the movie Constantine is described as more of a psychic than a mage but this is decidedly a case of to-MAY-to vs. to-MAH-to. In the movie he’s a damned soul because he successfully (albeit temporarily) committed suicide at the age of 13, thus tainting his soul with a mortal sin. This is also the source of his knowledge of the denizens of hell since his two minute terminal event was a subjective lifetime given the divergence between time in the mortal realm and in the spiritual realms.

The movie opens with a blurb regarding the Spear of Destiny (that being the spear that was used to pierce the side of Christ). We are told that whoever controls the spear has power over the world and that the spear has been lost since World War II. One would suppose that we would learn how it was lost, what was significant about World War II (Nazi occultists?) and some explanation of what the previous owners of the spear did with all of their presumable power. Alas, nothing more is forthcoming on that point. I suspect that we are seeing, in this blurb, the last elements of a previous version of the script that somehow escaped redaction. Be that as it may, the movie opens with two Hispanic men finding the spear underneath a decrepit building (does this happen in Mexico, in the United States, or elsewhere — the movie doesn’t say).

The mood of the opening scene is very reminiscent of the Smeagol and Deagol scenes, from The Return of the King, so much so that I half expected the man who found the Ring, er Spear, to start babbling about his preciousss. Fortunately, the movie quickly moves to a rather good exorcism scene involving a possessed girl, a pissed off demon, and a rather large mirror. Our hero performs the exorcism at the request of a priest who admits to being well over his own head in attempting to give this demon its deportation papers. The scene plays out very well — no joke. If the whole movie maintained this feel and tempo it might well have deserved to become a sort of kitsch classic. Alas.

Finally, we meet our female protagonist, Angela Dodson, a cop, whose twin sister has apparently committed suicide. Angela and her sister are both Catholic and believe that suicide is a damnable sin so Angela refuses to believe that Isabel would have done such a thing, in spite of the fact that she was living in a mental institution. After various false starts she hooks up with Constantine and, together, they start to unravel a demonic conspiracy with potentially (and literally) apocalyptic consequences.

There is a lot I like about this movie, actually. One of my favorite plots in the comics involved Constantine’s imminent death from lung cancer due to a lifetime of smoking and the very clever way that he got out of it by selling his soul not to one but three devils. The essentially elements of that plot were carried over to the movie (although the resolution is different) which I thought showed an actual awareness of the source material, which is more than one can say of all too many comic adaptations I rather liked the portrayal of hell as being a dystopian version of Earth, complete with rusted out cars and some very disturbing demonic hounds. I like the fact that they, at least, tried to portray Heaven although, as with most efforts, Hell is more compellingly interesting. Peter Stormare’s Lucifer was over-the-top, but in a good way, and Tilda Swinton brought an intriguingly androgynous ethereality to the half-angel character of Gabriel. I loved the supernatural nightclub run by Djimon Hounson’s character of Midnite and it’s psychic entry test (you have to guess what’s on the opposite side of a tarot-like card). There were also a lot of genuinely good effects scenes.

There are two things that bring the movie down, unfortunately: plot and acting. I know it’s fashionable to bash Keanu Reaves. Honestly, I think that there are roles that are well suited for him. His portrayal of Neo in The Matrix did a good job of offering us a man whose reality had been swept out from under his feet (at least until he went into Savior mode). Unfortunately, Constantine was not the right role for him. The Constantine of the comics is, above all else, an intelligent character who survives on his wits. Reaves can’t pull that off and the effort of watching him try was painful. Rachel Weisz was very nearly as bad. Her character was supposed to be strong and tough but came off as emotionally flat and mildly pissy. Since these two characters are the leads, we are stuck with watching them try to act their way out of a paper bag for far too many minutes of the movie. The script writers also made the inexplicable decision to give Constantine an annoying teen sidekick named Chas Chandler whose … and believe me, I kid you not… main function is to drive Constantine around in a cab.

As for the plot, it never quite gels and it never quite knows what it wants to d with its (undoubtedly enormous) budget. At its best, it evokes a sense of otherworldliness hiding in the corners of the mundane world but, at its worst, it becomes an incoherent video game. A case in point of both the former and the latter: one of John’s associates is a kind of supernatural arms dealer named Scavenger. He’s a very cool character. When we see him offering his wares to John, which including shavings of the bullet that was used in the assassination attempt on the Pope, water from the river Jordan, and a little box full of some demonically repellant bugs, I was intrigued and amused. Unfortunately, one of John’s acquisitions is a kind of crucifix-shaped shotgun that must have come out of the same armory that produced the Holy Hand Grenade of Antioch. Much later on when Constantine is blowing away a small army of half-demons with it, I felt like I was watching a very high-tech version of Quake II. This is not at all what the Hellblazer series was about and it’s a disservice to the character of Constantine.

As the closing credits rolled, I felt that I had sat through something that had a lot of potential and, most painfully, which had occasionally risen up to that potential but which had, ultimately, meandered and degenerated into something that was little more than an exercise in creepy eye-candy. Ah well.

1.46 out of 3.14 Nudnicks.